April 22, 2020 marks the 50th anniversary of Earth Day. In 1970, over 20 million Americans, or 10% of the population, marched to protest the widespread lack of awareness around human-created environmental damage.

Organizations like earthday.org convene efforts to keep human activity in balance so the earth can continue to support life – not just human life, but all species who share this planet.

Although this may seem like a novel idea, many cultures over much longer periods of time than that of our modern era practiced culturally-integrated environmental stewardship. In almost all examples, cultures recognized the role that trees played in balancing the earth and supporting civilization. This can be seen in the widespread presence of trees in mythology and cultural identity, and more recently, in research as scientists scramble to find ways to keep our planet habitable.

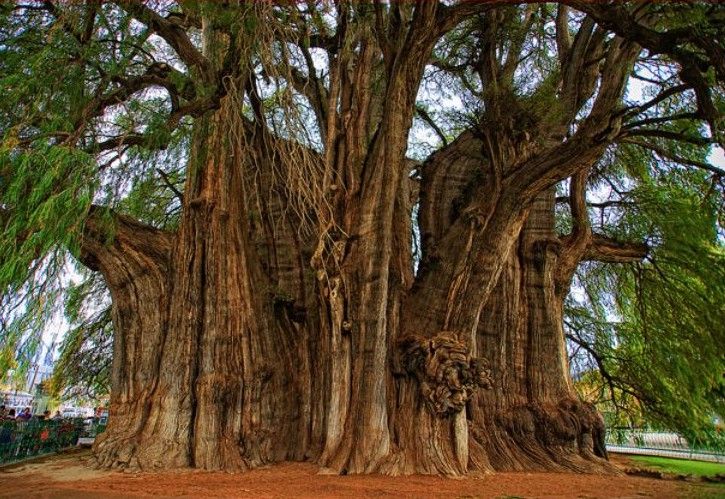

The Tule Tree, Oaxaca, Mexico (via Pinterest)

One of my favorite examples of a culturally sacred tree is the Tule Tree, located just outside of Oaxaca, Mexico. The Tule Tree is a Montezuma Cypress, estimated to be 2000 years old and just over 46 feet in diameter, making it the widest girth tree on earth. It has been the center of sacred culture for people in this area of Mexico for millennia. The Tule Tree is known as the tree of life because Oaxacan culture, like many other cultures, saw trees as the connectors between earth and sky and a representation of the generational cycle of life. Perhaps a more familiar popular example of tree-inspired culture is Vrksasana, known commonly by those who practice yoga as Tree Pose. Like all yogic asanas, Tree Pose models nature to create a movement practice that develops health for the practitioner. Tree Pose uses the characteristics of the tree, rooted in the ground and reaching to the sky, to create human balance and centeredness.

Water, Earth, Stone, Wood Collage

In the ancient design world, natural materials, including wood, were understood to bring forward the inherent properties of the material into the built environment. Fung Shui from China and Vastu Veda from India prescribed strategies for creating human impacts by combining these inherent properties in the design of spaces. Recent research hypothesizes that our human psyches and bodies have a pre-conscious biological response to the natural world and that we can use this knowledge to improve human health and wellbeing in the built environment. This practice is called Biophilic Design, and we use this approach in our all of our work, including Baker Hall at the Yale Law School.

Yale Law School baker Hall Courtyard Terrace

There are about three trillion trees on earth which not only provide for human mental and physical health, they also support the other 6.5 million land species that share this planet. Research demonstrates that walking in differing densities of tree canopies (or duration spent walking among trees) can create differentiated tension and stress reducing responses in our bodies. As we all know from our elementary school education, trees play a major role in producing the oxygen we breathe and they capture carbon dioxide. Carbon dioxide emissions are driving global heating, a significant contributor to climate change. As referenced in The Guardian in the last year, a worldwide planting program equivalent to 11% of the earth’s land area could remove two-thirds of the global warming impacts of human activities. Planting more trees, in addition to stopping deforestation, is the balancing act we must collectively accomplish to allow emerging economies to grow without creating the radical imbalance that mature economies did as they grew.

Image courtesy of The Government of Rwanda via Flickr

Trees (and plants too) can do even more to restore the earth through what’s called bioremediation. Bioremediation is the use of either naturally occurring or deliberately introduced microorganisms or other forms of life to consume and break down environmental pollutants. I recently read an article in the New York Times that describes how inoculated poplar trees are being used to clean up contaminated sites. At Moffett Field in the San Francisco Bay Area, inoculated poplars were planted in 2013 to draw carcinogens out of the ground. Each tree takes up to 50 gallons of toxic water a day and breaks it down into harmless chloride and carbon dioxide. The deep and spreading root system of poplars makes them an ideal fit for this task. Specific plant life needs to be matched with specific hazardous waste conditions, and bioremediation can take time, but it is a great approach compared to shipping hazardous soil or water off to some place to be stored (the most typical approach now).

Image courtesy of Protopian Pickle Jar via Flickr

Trees to the rescue, again and again. From a symbol of cultural significance, to ancient strategies that illuminate innate qualities, to our bio-wired healing relationship, to our scientific understanding of their remediation capacity, trees are a true wonder. Earth Day, even in this challenging time, offers a chance to reflect on and appreciate the best aspects of our interconnected world. With tension high and movement limited, now is the perfect time to get out for a quick walk in a park, or a hike in the woods, or to take a moment’s pause and a deep breath to enjoy the shadows of emerging leaves as they dapple light on the window. Any connection to a tree can bring healing and hope.

Header image courtesy of Marvin Foushee via Flickr